The Brutalist is the Most Anti-American Film of 2024

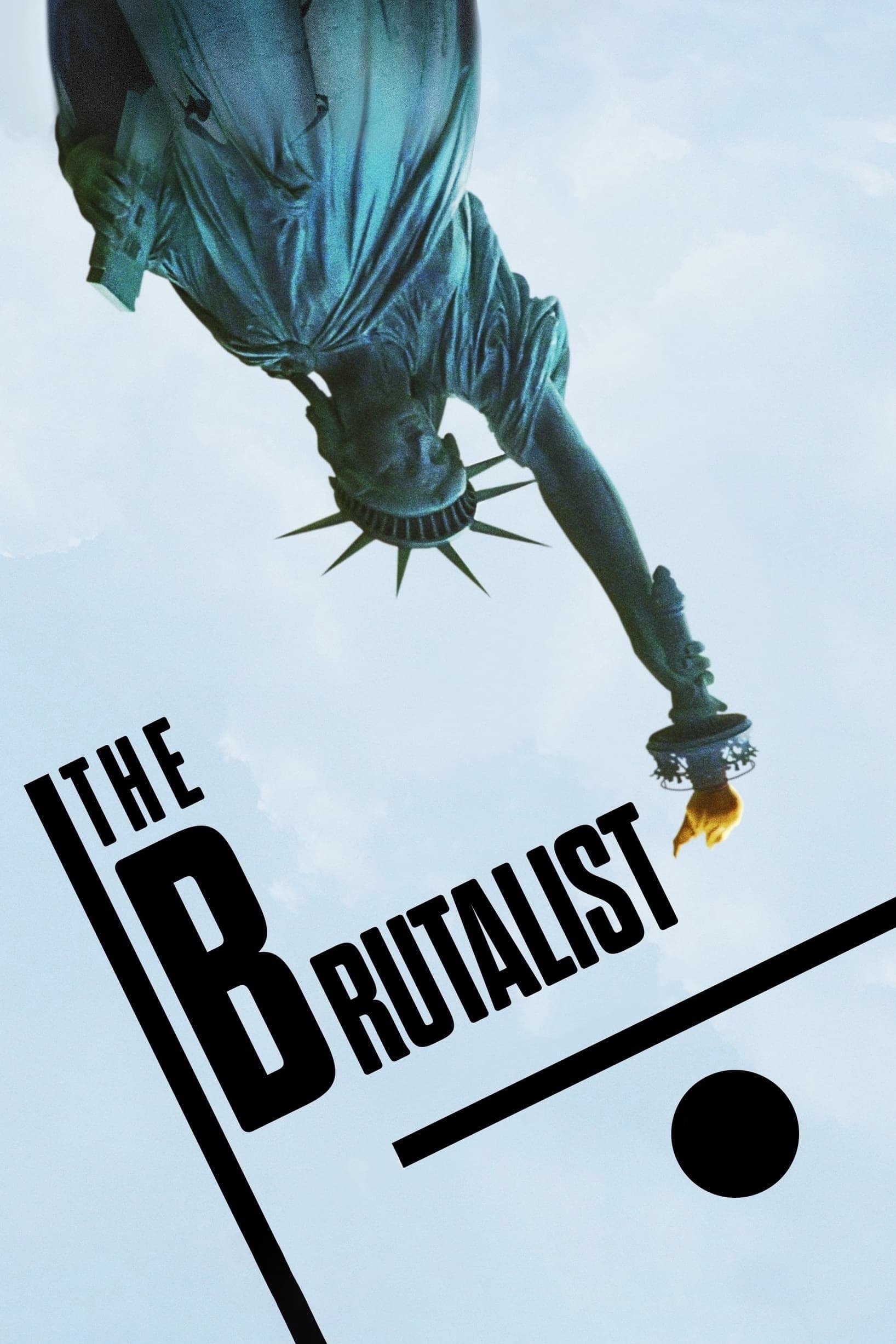

The Brutalist starts with an upside down shot of the Statue of Liberty. And that’s the most subtle metaphor in this film about the immigrant experience. It sets the tone for a film that never engages with its themes but instead reduces America, Christianity, and Capitalism to a clash of symbols. These abstract ideas collide without ever being fully explored, leaving the narrative feeling less like a human story and more like a morality play.

The Brutalist tells the story of Lazlo Toth, a Hungarian-Jewish architect who flees post-war Europe to rebuild his life in America. Toth comes into conflict with his patron, Harrison Lee Van Buren, a wealthy industrialist who wants to commission a community center from him. Thanks to Harrison’s help, Lazlo is able to bring his wife and niece to America. But all is not right in paradise, as the newcomers from Hungary clash with their rich American hosts, who are very Christian, racist, and antisemitic. If Corbet could’ve put a MAGA sign in their front yard and gotten away with it, he would have.

I feel like I have to pre-justify my own immigrant experience before diving into this incredibly cliched vision of the American dream. Like most immigrants, I came to America to get away from the past and make a new future for myself. Although I carry my heritage and my upbringing with me, I don’t let it hold me back, or use it as a sob story about assimilating into American culture. I would say most immigrants share that sentiment. They want to live a life of freedom, and they believe that’s possible in America more than anywhere else. You can work hard, and make a life for yourself and your family without question. So when I watched the Brutalist, every fiber of my being protested against the story shown on the screen. Still, I will try to judge the film as a work of art, and not as a documentary about America, but that does not absolve Brady Corbet from responsibility for his vision of America.

The Brutalist reflects a distinctly European critique of America, shaped by the director’s earlier work with directors like Lars Von Trier and Michael Haneke. Corbet’s vision of America is a country of religious philistines with too much money, who resent outsiders, yet claim to carry the torch of Western civilization. Through Laszlo Toth’s struggle as a Jewish immigrant, the film exposes America’s hypocrisy: a supposed refuge that demands conformity and strips newcomers of their identity. The film attacks the idea of assimilation, revealing the alienation immigrants face in a society eager to appropriate European sophistication while rejecting its progressive values. Corbet’s austere, brutalist aesthetic underscores his anti-American story, painting a portrait of a nation obsessed with wealth and power but lacking the cultural and intellectual depth it claims to embody.

After the first chapter, the film abandons subtlety for heavy handed allegory. Corbet’s preference for pitting abstract ideas—Zionism, capitalism, assimilation—against one another is exhausting. This clash of symbols not only feels contrived but detracts from the emotional depth that the immigrant story demands. New characters, and new events in the second half seem contrived to push the film’s message, instead of naturally arising from the plot, and from the conflicts of the characters themselves. While Toth is given a full hour for us to understand, the motivations of his wife and his niece are unclear, as if key scenes of the film are missing. Their moments are handled so bluntly that it feels less like character development and more like a checklist the characters are supposed to mark off.

Take the example of Toth’s black friend Gordon. They become friends on the breadline and Toth eventually hires him to work on his building. Gordon introduces him to jazz and heroin, but beyond that we know nothing about Gordon. Later in the film, a severely traumatized Toth fires Gordon summarily, which I suppose is supposed to illustrate how America and capitalism continue the cycle of abuse? It’s completely incoherent. Gordon simply exists to show that Toth is not a racist.

It could be argued that Lazlo Toth is not your typical immigrant. He’s a survivor of the Holocaust, dealing with mental and physical trauma, survivor’s guilt and PTSD. What I noticed about Toth in the entire film is that he fights with everyone. He fights with his cousin, with his wife, with his patron, with everyone. If this movie had only been about the trauma of a holocaust survivor, it could have worked better as a poignant portrait of Laslo’s life. But to borrow a phrase from Paul Schrader, “three hours is a long time to spend in the company of an angry man”.

In an interview with the Hollywood Reporter, Brutalist director Brady Corbet lays out his vision for the Brutalist:

“The film is about how the artistic experience and immigrant experience march in lockstep, which is to say that, in general, if someone moves into a suburban town in America and they don’t look like everybody else—because of the color of their skin or because of their beliefs or traditions—everybody wants theme to get the fuck out…. So, for me, Brutalist architecture is representative of something that people do not understand and that they want torn down and ripped away.”

These are poignant words from an artist, but they are not the words of anyone who’s actually lived life in suburban America. Even in the 1940s, Pennsylvania wasn’t as crude and brutish as Corbet seems to want it to be. Harrison Lee Van Buren is a stereotype right out of a Soviet play — angry, racist, predatory American who wants to possess Lazlo’s talent. Had the tension between the Van Buren’s and the Toth’s been about that, this could be a halfway decent movie. But the film descends quickly from stereotype into caricature. Harrison Van Buren’s son assaults Toth’s niece, and Van Buren rapes Lazlo in a quarry of italian marble, because rich Americans are monsters…GET IT? And if you didn’t get it, Van Buren explains why he’s raping Lazlo like a monologuing villain.

What have you done to yourself? It’s a shame seeing how your people treat themselves. If you act as a loafer living off handouts, a societal leech, how can you rightfully expect a different result? You have so much potential and yet you squander it….Who do you think you are? Who do you think you are? You think you’re special. You think you flow directly above all those you encounter, because you’re beautiful, because you’re educated. You’re just a tramp. You’re a lady of the night. You’re just a lady of the night.

Lazlo’s wife Erzbet is similarly written free of human complexity. She’s resigned to her husband’s impotence, his toxic relationship with Van Buren, and his angry mental state. The only contact they have with each other is when he injects her with heroin to dull the pain from her osteoporosis. If that subtext wasn’t subtle enough for the audience, Erzebet, who survived the horrors of the extermination camps in Europe says this about America: “this whole country’s rotten!”

There’s no subtext, it’s a full on rhetorical assault. What’s Erzsébet’s deal? Is she a nagging shrew, or is she an intellectual like Toth? We’re never given time to understand any of that. The film effectively ends when Erzebet returns years later to courageously denounce Van Buren in front of his family, resulting in Van Buren ending his life off-screen. By this stage in the film, the audience is already fatigued by the film’s relentless moralizing and bleak tone. This moment feels like a sledgehammer blow to end a point that has already been made—repeatedly.

The epilogue has sparked discussions from many critics, trying to make heads or tails of the film’s final message. The film’s tendency to strip its subjects of complexity is present once again, turning Israel into another symbol in an endless morality play. Lazlo is now an old man living in Israel. He’s unable to talk about his life’s work, the most famous being the community center featuring a giant cross, which is really a replica of a concentration camp. And in a final act of indignity, the niece who never agreed with him on anything is the one who speaks for Lazlo. Another boost of cynicism by Corbet, having exhausted all other metaphors, of the power of art and the role of the artist.

Corbet’s America is a place with no redeeming qualities, no contradictions, no complexity—just a flat landscape of oppression and ignorance. The film positions itself as a critique of the immigrant seeking the American dream, but it lacks the courage to explore the real tensions and compromises that come with that experience. It’s content to sneer from up on high, casting America as a place where art and identity go to die.

Member discussion